By Jessica W. Chen

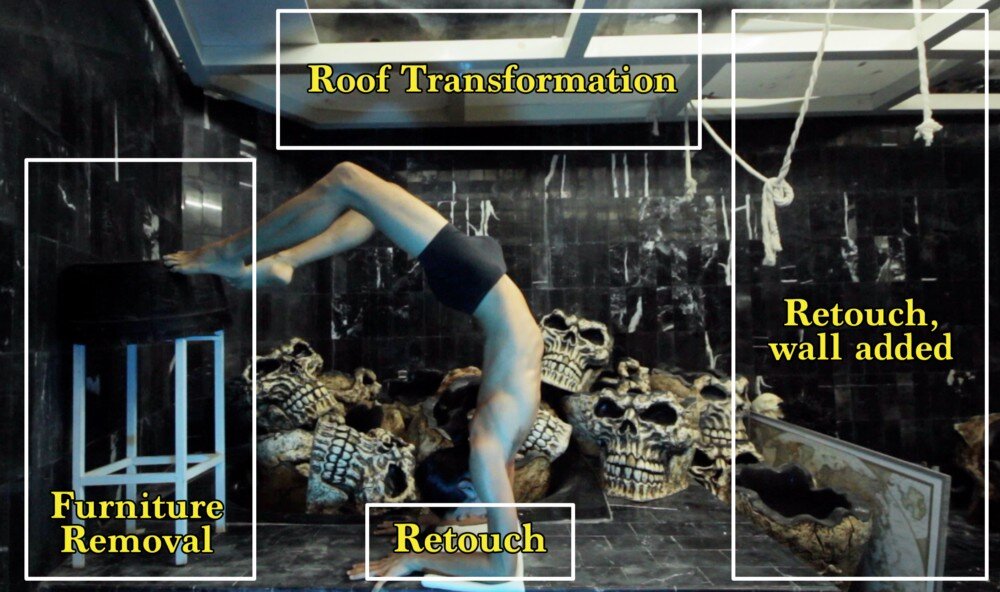

Actors Winter Dunn and Craig Fishback on the set of the short film, It’s Who You know. Photo by Adrian Gutierrez.

Recently, I rewatched Mulan (2020) in preparation to record a podcast episode for Re-Casting the Movies, a non-profit that challenges people to think outside the box for casting. While I was viewing the film for the third time, I couldn’t help but ponder whether the lack of Asian or Asian American screenwriters played a factor in the movie’s notable cultural inaccuracies and Mulan’s unrelatable, inauthentic character.

As a writer, it’s often comforting to write what you know, without having to worry about inaccuracies or potentially appropriating someone’s culture. And, given the racial, ethnic, and class make-up of the majority of writers rooms, that explains why onscreen characters that aren't cis, white, upper-middle-class, straight, and/or non-disabled are still a rarity.

For evidence of how writers rooms don’t often reflect the world at large, consider a 2017 Color of Change study that found that “Fewer than 10 percent of the shows were led by minority showrunners, and only 14 percent of writers across all shows were members of a minority group.” And, a report conducted by GLAAD found that while the 2019-20 season of scripted broadcast programming reached a record high of 3.1 percent characters with disabilities, this was not representative of real life, as over 20 percent of people in the U.S. have a disability. These issues are structural and multi-layered but can be partially addressed in the writer’s room.

This makes me think back to the November 2019 writers’ room I created for Lil Swimmers Production’s Existential Crisis Club, a dramedy series about four 20-somethings who struggle with planning an alcoholic bubble tea bar's opening while grappling with the crushing existential dread of having life together by age 30.

In this series, one of the four 20-somethings is Gabe, a gay man who struggles with his love life. When I led the writers’ room that wrote Gabe’s story, I wanted to be sensitive and truthful to the gay male dating experience. As a straight, cis-woman, I knew this meant expressing and dealing with unique challenges, most of which I wouldn’t necessarily be familiar with.

So, how did I do this? Here are the seven steps that I learned about how to staff a writers’ room that can write diverse characters:

Step #1: Staff the writers’ room consciously

I’ll admit that I kind of failed at this part for Existential Crisis Club because I had initially populated the writers’ room with my close writer friends without thinking too hard about staffing consciously. Thankfully, I’m friends with people from a variety of backgrounds. Upon further inspection, I realized that out of six writers, half identified with being part of the LGBTQ community, which worked well for telling Gabe’s story.

More recently, when I started from scratch and formed the writers’ room for Drama High, I knew better. I took care to assemble a group of writers who I knew came from different life experiences and could bring something unique to the table. Despite Drama High being a love letter to Asian dramas, I made the decision to also recruit writers who weren’t Asian or Asian American. The writers who weren’t Asian or Asian American were still Asian drama fans, which I find invaluable since international drama fans need a voice in our room, too.

Step #2: Consider hiring cultural advisors

This tip may be more aimed toward higher budget productions. However, if you have the resources, then hiring cultural advisors is a smart investment for helping your writers tell more authentic stories that are respectful to the communities you’re drawing from.

You may have heard how Disney put together the Oceanic Trust, “a group of anthropologists, cultural practitioners, historians, linguists, and choreographers from islands including Samoa, Tahiti, Mo’orea, and Fiji,” to serve as cultural advisors for Moana. Or, even science advisors for Marvel movies. These subject matter experts (SME) act as consultants to help steer productions away from inaccuracies that may distract from the story or cause offense.

Step #3: Hire more than one voice per experience

While you may not want to have more than ten writers in your writers’ room, be sure to hire more than one voice per experience you want to tackle to prevent tokenism. Tokenism involves “including someone in a group purely for the sake of sounding or looking diverse.”

Hiring more than one voice per experience keeps in mind that not everyone with a particular experience has the same experience. For example, consider that “the Asian American experience” covers an enormous range of ethnicities, socioeconomic statuses, and generations in the U.S. Therefore, if you’re writing a story that purports to relate “the Asian American experience,” first of all, get more specific. Which cultures and languages have the character been exposed to? What’s their socioeconomic status? From there, it helps if you have more than one Asian American writer in the room who can contribute their unique perspectives, and have the experiences that allow them to relate to the character they’re writing. You’ll find that having more than one voice per experience helps you hit closer to the truth. Human experiences are complicated, and having multiple viewpoints uncovers those nuances.

Step #4: Cultivate openness, honesty, and trust

The most effective stories touch upon relatable truth. To get at these truths, your writers must be willing to bare their souls and bring their lived-in experiences to the table, even if they’re not pretty or heartwarming. Getting your writers to this vulnerable position requires you, the showrunner, to cultivate openness, honesty, and trust, whether that’s through enlisting your close friends, as with Existential Crisis Club, or taking the leap and sharing your own painful stories first, as with Drama High. Whatever you choose to do, your writers must feel safe to share their stories, and it’s your job to get them there.

Step #5: Listen actively when writers share stories

When writers share their experiences, show you value your writers’ contributions by listening actively when they share their stories. This can be difficult to convey if you’re holding your writers’ room virtually like I am due to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, during the video calls, I ask my writers to note down their ideas in a shared Google Doc after speaking, so I can stay focused on the writer when they’re telling their stories. Oftentimes, I ask clarifying questions or elaborate on how their stories relate back to the characters to show I’m working their ideas into the script. These little gestures illustrate that you hold your writers’ time and efforts in high esteem, which makes them more comfortable with sharing further.

Step #6: Conduct yourself with empathy

Not every story is an encouraging one, and some may even be tough to relate to. Thus, it’s crucial to set an example for the rest of the room and conduct yourself with empathy. Be sensitive when writers tell stories that may be painful or triggering, and warn others if you’re about to discuss one. Put aside any entitlement you may feel towards knowing someone’s story because if that writer is uncomfortable with talking about a part of their life, then you must let it go. Pressuring your writers to share won’t raise the morale of your room, and will only show that you don’t care to respect boundaries.

Step #7: Aim for truth, but do so with dignity

A writer's personal bias often affects how a character's story is told through editorializing. Editorializing is when the writer introduces their own personal opinion on a subject when writing about that subject, often through the use of words with specific connotations or the way they speak about the subject.

When writing a character whose lifestyle or decisions may not match yours, do so in a way that shows empathy for the character and affords them dignity. Even if the experience has some elements that you consider “seedy” or causes you to place judgment on it for whatever reason, attempt to discuss the experience evenhandedly. After all, if you can’t even be respectful to your character, then why are you trying to tell their story? There must be a writer out there that can do the character justice, so give the story to them instead.

Now that we’re entering 2021, it’s about time writers learned how to incorporate experiences that aren’t their own into their writing. With these steps in mind, showrunners will be able to staff and run writers’ rooms that are one step closer to delivering characters that let audiences experience new American stories that showcase the intricacies of our diverse society.

Find out more about Jessica W. Chen and her work at her website. Or, follow Jess on Instagram, Facebook, and Youtube.

If there are other questions you want to be answered in a blog post, let us know at info@fourwindfilms.com or visit our website at www.fourwindfilms.com. Also, we work with a large, diverse community of crew and artists working in most aspects of the filmmaking process and are always happy to help make connections. And we are always building our community! Send us your work for review or feedback.